Illustration by staff illustrator Sakura Siegel.

It’s 10 a.m. on a sneaker’s release day. Andrew Macatangay — like thousands of others — just entered Nike’s raffle for a pair of Off-Whites, and in five to 10 minutes, the app tells him whether or not he got it.

The screen goes white with a photo of the Off-Whites and he’s greeted with “Got ‘Em” — a message not too many sneakerheads are blessed to see.

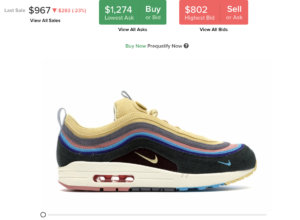

But Macatangay is one of hundreds who doesn’t always keep the shoe. He instead puts them on resale, which a pair of Off-Whites can go for $1,459 on StockX, instead of its original $190 retail price.

But to understand a Filipino hypebeast, Macatangay says to look at the deep roots of the Philippine’s history: their poor, urban area, escape to basketball and connection to hip-hop.

But First, The Hypebeast Lifestyle

Macatangay, 21, says he’s not a “hypebeast,” but is a “shoe enthusiast.”

A “hypebeast” is someone who aims to get fashionable pieces, specifically clothes and sneakers, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary.

Clothing brands like A Bathing Ape, Supreme and KAWS are high on this community’s radar while sneakers like YEEZY, Air Jordans and Off-White have them wake up early to snag a pair either through virtual raffles or camping outside of a store — pre-coronavirus.

Famous Filipino celebrities like Billy Crawford and Vhong Navarro have worn sneakers like Off-White on their show, “It’s Showtime,” which airs on The Filipino Channel (TFC). Crawford has also showcased his collection on social media.

https://www.instagram.com/p/3xdER7JO_0/?utm_source=ig_embed

“Whether they’re ‘hypebeasts’ who collect limited-edition reissues of classic styles, aficionados interested in predominantly vintage sneakers or casual collectors who like what looks good to them regardless of a shoe’s resale value, sneakerheads see no reason to wear any other type of shoe,” Susan Carpenter of The Los Angeles Times wrote in 2006.

Macatangay owns a Depop shop and sells used and deadstock — never worn — clothes, sneakers and collectibles. He said “hype” comes from well-known brands and celebrities who sport it, which drives prices up. Since he was young, that’s how he made money, and now he flips — resells — sneakers to buy things he wants.

The Philippine native said his prized shoe is the Sean Wotherspoon Air Max 97, which came out in 2018 and its resale costs about $1,300; a used pair is between $800 to $900. He got a pair for $500.

“Sneakers is better than kids getting into drugs to be honest,” Macatangay said. “I’d rather personally see my kid spend money on something they’d use and can make a decent profit of.”

And for millions of Filipinos that’s the problem — it’s a challenge to earn cash, so many resort to other means.

Ingredient #1: A Filipino’s Struggle

Macatangay was born in the Philippines, but now lives in Belleville, New Jersey. His mom is from Antipolo, Rizal while his dad hails from Taal, Batangas.

Though Rizal and Batangas are two of the least poor provinces in the Philippines, the country is still riddled with low economy, malnutrition and crime. The nation’s overall socioeconomic status can be linked to many problems including its drug crimes.

Historically, the Philippines is a third-world country. In 2019, minimum wage was raised to 537 pesos a day, which is equivalent to $10.

A spokeswoman for the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse told Polifact in 2017 that survey data showed there’s higher drug usage among people living in poverty compared to those with higher incomes.

There are 1.8 million drug users in the Philippines and 4.8 million Filipinos have said they used illegal drugs at least once in their lives, according to the Dangerous Drugs Board, a Philippine government agency who handles policies on illegal drugs.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte took office in 2016, and since then he’s declared a “war on drugs,” a campaign that’s left over 12,000 Filipinos murdered, no matter the age, because they were suspected as users, producers and suppliers.

But like many poor inner-city kids, basketball and hip-hop offers a place off the streets.

Ingredient #2: Basketball As Their Safe Haven

Ivan Aquino, 20, said he’s been surrounded by basketball since he was a baby.

He grew up watching his dad and older siblings play pick-up at Lincoln Park in Jersey City and then subbing into school basketball games. Aquino joined his first team in the sixth grade.

“Basketball is a tradition in the Filipino-American community,” he said. “And it’s all over the Philippines.”

The Philippines was originally a Spanish colony, but after the Spanish-American War, the nation was annexed by the U.S.

Teachers from America introduced the sport in 1910. It was initially intended for girls for their physical education curriculum because baseball and track and field seemed too intense, SLAM Online PH reported.

But then the activity spread like wildfire across the nation, and not much has changed since. The Philippines is home to the Philippine Basketball Association (PBA), the second oldest of its kind in the world and Asia’s first professional basketball league.

Today, basketball courts and hoops can be found almost everywhere in the country — whether it be hung on run-down houses in poor provinces, hidden between abandoned warehouses or showcased in the richer parts of the nation.

And Aquino says the one professional basketball player that kept the Philippines going was Kobe Bryant.

“Kobe plays a big part to us Filipinos in inspiring us to play,” Aquino said. “… Have a Mamba Mentality of having confidence and resilience in not only the game of basketball, but in life itself, taking every shot like it’s your last.”

Bryant, the legendary retired Los Angeles Laker, died in a helicopter crash in January in California. His 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, also died in the accident, as they were on the way to her basketball tournament at the Mamba Sports Academy.

A day after the fatal incident, an enormous mural of Kobe and Gianna was painted on a basketball court in Metro Manila, where Aquino’s family comes from.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B73C0OxgxhF/?utm_source=ig_embed

Bryant made several trips to the Philippines. Two years after the late Hall of Famer was drafted, he did some traditional Filipino dancing at an event during a visit.

But over the last two decades, basketball and its players are no longer a singular thing — it’s meshed with hip-hop and its artists, creating a cultural marriage, Zu Media said.

Ingredient #3: Hip-Hop As Their Emotion

“It wasn’t that Filipino immigrants were drawn to 90’s hip-hop,” Joey Marana wrote on Plan A Magazine. “It was a history and culture and spirit of a people that were kindred with those that created this culture and art form that synced with each other.”

Spain conquered and colonized the Philippines from 1521 to 1898. Filipino indegenious tribes were hammered down by colonizers as their warrior (or tribe) practices, clothing and fighting styles were chipped away.

But Filipinos held onto their fighting techniques and movements through dances. They kept grasps on their traditions as many immigrated to California in the early 1900s. It was here where Filipinos connected with the African and Afro-Latino communities who were also combating oppression and seeked an escape.

Their antidote? Hip-hop.

“The classic elements of hip-hop culture were direct reflections of a Filipino history once rich with tradition,” Marana added. “Tinikling dancing and Eskrima footwork, to six stepping and uprocking.”

Fast forward to now, over 100 years later, and traces of Eskrima — Philippines’ national martial art — can be found in modern Filipino- or Asian-American b-boy groups, a team of hip-hop breakdancers.

“B-boy is super big in the Philippines and it’s mad influential,” Macatangay said. In 2018, four Philippine dance groups won medals at the Hip Hop International (HHI) World finals, a competition where high-profile dance teams meet. HHI is also the producer of “America’s Best Dance Crew,” where the Jabbawockeez — a famous Asian-American team who includes a Filipino-American — won the first season.

Jeffrey Lorenzo Perillo looked at “Hip-hop, Streetdance, and the Remaking of the Global Filipino” in a dissertation for the University of California. Perrillo wrote: Hip-hop dance is part of a repertoire for racial subjectivity of Filipinos; decolonization is tied to hip-hop’s institutionalization; and dance offers an alternative perspective of hip-hop’s globalization.

“Hip-hop gives us a way of expression where most of us Filipinos cannot (express in other ways),” Aquino said.

But hip-hop doesn’t only heal through choreography, but music too.

“The country is producing a number of rock/alternative musicians and even rap music has entered the Philippines,” Paul A Rodell wrote in Culture and Customs in the Philippines.

Indigenous music lives on in the Philippine provinces through local brass bands — marching bands — and rondalla music — a group who performs with stringed instruments. But now, some Filipino rappers are moving up the ranks at home, though none have yet to break the scene in the U.S.

Bawal Clan — “bawal” meaning prohibited or not allowed — released their first album “Paid in Bawal” in 2018. “R U Aaliyah?” an R&B-style song on their debut album, is their top hit with over 3 million plays on Spotify. But “Yoga Flame,” which is also on their first project, is their third-top hit; the beat and flow can be traced to its West Coast rap influence.

Lyrics from “Yoga Flame”:

Got the fiends askin my peeps

“Yo where the crime at?”

Ano yun, walang jo

So just go rap nalang

Sige lang trap ka jan …

U dont even trap naman

Lang alam, no ba yan

Ayus lang tumupi

Tumabi. Wag pilitin pwede ng umuwi

Translation:

Got the fiends askin my peeps

“Yo where the crime at?”

What’s that, nothing

So just go rap

Go ahead, trap over there

You don’t even trap really

Just know, is that it?

It’s okay to fold

Step aside. Don’t force me to go home

“Hip-hop culture at its core, is built on values of social justice, peace, respect, self-worth, community, and having fun,” The Conversation wrote in 2017. “And because of these values, it’s increasingly being used as a therapeutic tool when working with young people.”

After 1965, Los Angeles became one of the largest U.S. cities that Filipino immigrants called home, especially Filipino youth. Here, they were introduced to not only hip-hop/rap, but fashion too.

Ingredient #4: Streetwear Is Their Identity

Jared Ammugauan is a college student from Jersey City, but most locals know him as 201.thrift, his Instagram account where he curates vintage clothes and other streetwear. The account has 2,275 followers.

“Most of my followers on my page consists of Filipino-Americans, and one thing I’ve noticed is how branded pieces are sought after the most,” Ammugauan said. “Particularly vintage Nike, Tommy Hillfiger and Polo Ralph Lauren.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CAMH5dOhj9q/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Even in the ‘90s, Filipinos seeked brand-name clothes like Tommy Hillfiger and Nautica, which was also circulating the hip-hop scene in America at the time. Clothes played a role in how Filipino youth — especially in inner-city areas — identified themselves.

But it was the Filipino street gangs who marked the importance of identity by clothing.

The Satanas were one of the more prominent street gangs in the Filipino-American community during the 1970s. They were the “defender of the Filipino” as they protected their reputation against Latino gangs in Southern California.

Aside from crime and violence, gang warfare set the path for fashion.

Filipino gang members adopted Latino gangs’ cholo style mixed with jefrox, a Rock-inspired style popularized in Manila. Later, Filipino youth would fully adopt cholo fashion with loose fitting, baggy pants and baggy shirts with necklaces.

“We’ve been inspired, influenced and entrenched in these other cultures, so it’s only natural that Filipinos would include this hypebeast/streetwear culture,” Ammugauan said.

Poverty → Basketball → Hip-Hop → Streetwear = A Filipino Hypebeast, The Final Product

The equation isn’t perfect, but Ammugauan, Aquino and Macatangay agreed that basketball, hip-hop and streetwear are connected to the creation of a Filipino or Filipino-American hypebeast.

“There are large populations of Filipino-Americans living in inner-cities…,” Ammugauan said. “Within these urban areas, there’s a lot of diversity and people of color… While we have different experiences culturally, we tend to share an element of struggle that binds us together.”

Hip-hop stemmed from poor, urban neighborhoods. Basketball thrived in poor, urban neighborhoods. Streetwear was admired in poor, urban neighborhoods. Because of the Philippines’ historical poverty, many Filipinos have seeked an escape through one of the three.

And even if a person of Filipino heritage didn’t grow up in the slums of the Pacific Island, a piece of hip-hop, basketball or streetwear has been carried and passed on from someone in their family or close friend group — like Aquino with basketball, Macatangay with sneakers or Ammuguan with clothing.

None of the three call themselves hypebeasts, but they said they’re aware of the role minorities have in this urban community.

“In a cultural aspect, the greatest thing hypebeast culture has done is bring streetwear to light within the past several years,” Ammugauan said. “And has given opportunities to minorities and people of color.”

He says examples are Virgil Abloh and his collaboration with Off-White; Michael Jordan and his revolutionary Air Jordan brand; and Travis Scott, whose sneaker collaborations have shot up in resales.

But still, why sneakers?

The simple answer — basketball, hip-hop or streetwear. Take your pick.

“Basketball is a popular sport in the Philippines and amongst Filipino-Americans,” Ammugauan said. “It’s ingrained into our culture and naturally sneakers and jerseys are a part of that.”

“In many (hip-hop) music videos, there’s some affiliation with basketball,” Aquino added.

Take “Trade It All Part 2” by Fabolous for example. Jerseys and Nike sneakers ruled hip-hop in the early 2000s and 2010s. In this 2002 music video, Fabolous is sporting Kobe Bryant’s No. 8 jersey.

In 2016, Filipinos were a third of the Golden State Warriors Facebook fans, a team who was running the show in the NBA at the time.

“(Because of basketball and hip-hop) it’s not really hard to influence Filipinos in like streetwear/hypebeast culture,” Macatangay laughed.